|

DRAGONETS

by Jane Lilley

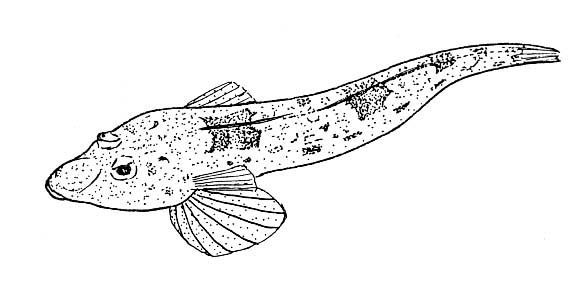

Protruding Eyes

Like many other bottom-living fish, Dragonets have wide heads with protruding eyes set on the top where they give all-round vision. Seen from above, the head is almost triangular, with a pointed snout, and the body tapers steadily backwards to the tail. The underside is flattened, for resting on the sediment, and at times they will bury themselves. I have watched them shuffle sediment out rapidly from under the body with their big splayed pelvic fins (the ones underneath the body, just behind the head) so that they sank down into the sand; after a few seconds only the eyes were visible.

Most fish have gill slits on the sides where the head joins the body. To breathe, they draw water in through the mouth, pass it over the gills, and push it out through the gill slits; a one-way system, much more efficient than our in-and-out breathing. But in a buried Dragonet, the sediment would obstruct the flow of water out of the gill slits, and to avoid this, the gill openings have become holes almost on the top of the head.

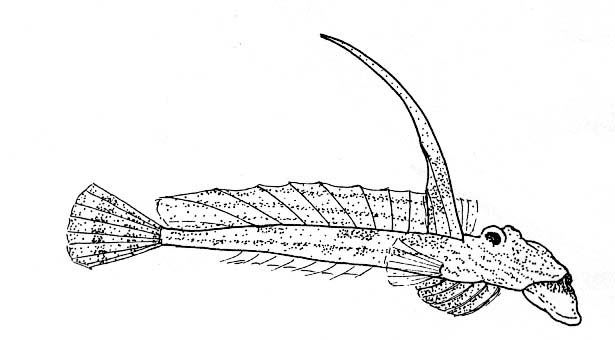

One distinctive feature is a very tall triangular fin on the back, with a normal fin behind it. This is larger in mature males than in females and young dragonets, but is distinctive even in small fish. Unfortunately for divers trying to identify the fish, the fin is usually folded flat onto the fish's back, so its distinctive shape cannot be seen. More visible are the big pectoral fins, on either side just behind the head.

Size and Colour

Although most of the Dragonets you see are small, they grow quite large: females can reach 20 cm (8 in) long and males grow up to 30 cm. Youngsters of both sexes, and adult females, are neutral beige--brown in colour, but adult males much more are brightly coloured. According to books, they are quite spectacular, with bright blue stripes and spots all over the yellow body and fins, and look so different from the females that they were originally thought to be a different species. Unfortunately they are rarely seen by divers - or frequently overlooked. Probably, like a number of fish species, they can alter the intensity of their colouring, so that the colours are relatively muted most of the time, and when they rest on the sediment with their dorsal fins folded, they are almost as inconspicuous as the females. Only when trying to excite a female would the full colours be seen. Even then, they may not be spectacular. The only time I saw a recognisable male, in an aquarium, it was displaying without much enthusiasm to a totally disinterested female, and its colours were not impressive; they would probably have become brighter if the female had responded.

It is also possible that Dragonets only breed once, at the end of their lives. As the life span is considered to be about seven years for females and five for males, and huge numbers will fall victim to predators before they reach breeding age, the proportion of mature males would then be very small, and your chances of seeing one not very great.

Bionomics

Their courtship is quite elaborate, which is unusual in British fish. The male I watched approached the female, then spread his pectoral fins and erected both dorsal fins, showing off their colours, at the same time lifting his head and opening his mouth very wide; he did this repeatedly. Had the female responded, the courtship would, I am told, have continued with increasing excitement until the two fish swam vertically upwards, undersides together with the female resting on the male's pectoral fins, and released their eggs and sperm to be fertilised between their bodies before it drifted away.

Dragonets are reported to eat a range of small animals which they find in the sediment, including worms, small shrimps and other crustaceans, and little bivalve shells. I have watched one swimming just above the bottom, its protuberant eyes swivelling as it looked all round; at intervals it pounced suddenly on a tiny crustacean I could hardly see. They are also said to gulp mud and puff it out from the gills, probably filter-feeding.

The fish you are most likely to confuse them with are the Sand and Common

Gobies

(which are almost impossible to tell apart from each other); these are

found on the same type of sediments, resting on the bottom, and swimming

in short dashes. But the gobies are a much more uniform colour, with darker

speckles instead of clear saddles and blotches; their bodies are rounded

underneath, not flattened, and they do not have the triangular heads of

Dragonets.

Male

dragonet 'displaying'

Dragonets are small fish which are extremely common on sediment, and I must have seen hundreds of them. Females and juveniles are patterned in drab brown and beige shades, very cryptic colouring on most seabeds. Males in breeding colours are supposed to be quite spectacular, with an enormously high, triangular anterior dorsal fin and bright blue stripes and blotches on the body; so they should be easily spotted, and it puzzled me that neither I nor anyone I knew had ever seen one.

One possibility is that they die after breeding. A recent book says that they are thought to do so. When I asked the National Marine Aquarium, however, they were definite that males neither died after breeding nor lost the long dorsal fin, though they said that the colours are usually muted, and ‘turned on’ in a second or two when they are actually displaying - something I have seen in another aquarium. So it sounded as if they should still be easily recognisable, but it remained possible that they spent most of their time buried, or moved into deep water outside the breeding season.

I still cannot give a definitive answer, but in late June this year I finally saw a male dragonet. He was in less than 12 metres of water, and not buried at all; but even so I almost overlooked him. I only gave him a second glance because of his unusual size - about 11 inches long. The front dorsal fin was certainly enormously long, but folded flat along his back in the normal fashion for a relaxed dragonet, slightly offset so that it lay beside, not on top of, the second dorsal. The male colours were present when I looked closely, but they were so faint that they were barely detectable.

Probably, like a number of other fish species,

the colours of male Dragonets become more obvious in the breeding season,

and intensify further when the fish is excited. So the bright colours shown

in some books are misleading; they will only be visible when the fish is

actually displaying, which is most unlikely to be when a diver is around.

For most of the year, male dragonets are probably around, buried some of

the time, and unremarkable and easily overlooked

|

|

|

|

|

News 2018 |

Membership Form |

|