|

Mass mortality of the Heart Urchin, or Sea Potato, Echinocardium cordatum, is well known to occur at times. The explanation usually given is that they have been killed by severe storms which have disturbed the seabed, first burying the urchins deeply enough to suffocate them, and later exposing them again, either throwing the dead urchins or bare 'tests' (the thin white shells that reveal the heart shape) on to the shore, or leaving them lying on the seabed. However, whilst working on the Sussex Seasearch forms I found reports which show that there may be another cause of occasional mass mortality.

The weekend of 6-7 May 1995 was very calm, with water temperatures of 13° C - 14° C, and a very thick plankton bloom extending from about 2 metres below the water surface to the sea bed. A number of Seasearch dives were made over a distance of about 7 km between Brighton and Peacehaven off the East Sussex coast, at depths ranging from 3.3 metres to 17.1 metres below Chart Datum, mostly over sand.

May 1995 Mortalities

A very high proportion of the dives recorded Echinocardium on the surface of the sand at densities of up to 20 per square metre, many dead or dying, others alive but partly exposed or only just below the surface.

There were apparently very local variations: one dive recorded few dead

urchins although many were 'ploughing' just below the surface so that each

left a furrow as it moved along, while another dive made at the same time

and only about 100 metres away recorded many dead urchins.

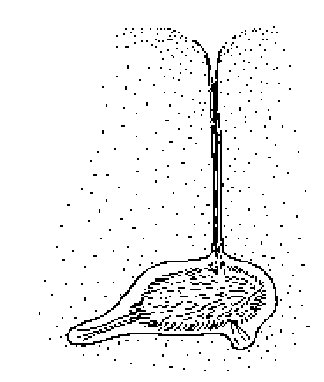

Heart Urchin in burrow

Heart Urchins

Echinocardium is usually found at depths of about 2 cm to 7 cm below the surface of the sand, and its presence is recognised mainly by the characteristic funnel-and-hole above it marking the top of its respiratory opening, through which it draws down seawater containing oxygen. Heart Urchins on the sediment surface are unusual; on two dives I made in the same area in September 1995 Echinocardium were abundant below the sand surface, but only one dead individual was seen and there were no live urchins on the surface.

The most likely reason for the mortality, suggested by Sussex Seasearch co-ordinator Robert Irving, relates to the weather conditions and the plankton bloom. Temperatures had been generally warm for the previous two weeks, and became hot on 4th May, probably resulting in a steady rise in sea temperatures until they were high enough to cause a very thick bloom of Phaeocystis plankton. With the calm sea preventing any mixing of the water layers and reducing the gas interchange at the water surface, decay of the plankton could have caused deoxygenation of the water close to the sea bed, first forcing the urchins to the surface of the sand in search of water with more dissolved oxygen, and if conditions did not improve, then suffocating them.

It is interesting that no other burrowing or surface-living species was recorded as reacting in a similar way; Masked Crabs (sometimes known as Unicorn Crabs) Corystes cassivelaunus, Razor-shells and other sand-dwelling species appeared to be behaving normally. If the cause of the mortality in Echinocardium was oxygen depletion, Heart Urchins must be the most sensitive of the common sand-burrowing species to reduced oxygen levels.

A large stranding of Heart Urchins, or Sea Potatoes, Echinocardium cordatum, occurred off the west coast of Scotland on including Troon and also Prestwick Beach. They were not freshly dead as the tests had lost their spines. The tests washed ashore in the gales.

Oxygen in Seawater at Different Temperatures

Sussex Seasearch is the scheme to record the sublittoral habitats of the Sussex coast. The participants are divers interested in marine life. It is organised by English Nature (Joint Nature Conservation Committee) with help and finance from the Marine Conservation Society.

For further information contact:

Robert Irving, 14 Brookland Way, Coldwaltham, Pulborough, Sussex, RH20 1LT.

Tel: 01798 873581 or David Harvey,

English Nature Tel: 01273 476595.

Chart Datum is the lowest astronomical tide from which depth soundings and tide levels are referenced.

Phaeocystis

Phytoplankton Blooms

Phaeocystis is a minute organism which can reproduce to enormous numbers, and is an example of the phytoplankton. Phaeocystis 'blooms' are called by names like Slobweed and Slurry Water, and are an annual occurrence off the Sussex and Kent coast in May and June.

During the day the phytoplankton photosynthesise and reproduce, the phenomenon called 'blooming'. The greatest 'blooming' occurs in the brightest sunlight which is associated with hot weather and higher sea temperatures.

Photosynthesis of the phytoplankton produces oxygen, which can supersaturate the surface waters of the sea. However, at the later stages of the phytoplankton blooms the nutrients they need are exhausted and the algae die and sink to the bottom where they decay, a process which uses up oxygen and creates hypoxic conditions (a deficiency of dissolved oxygen). There are many records of plankton blooms causing mass mortalities of benthic fauna.

Phaeocystis is a prymnesiophyte

flagellate that reproduces by fission at a phenomenal rate and forms large

colonies of cells about 1 mm in diameter.

Notes:

Another possibility is that Heart

Urchins are unduly sensitive to toxins produced by the live or decaying

plankton. However, if this is the case, it is not clear why they should

rise to the surface rather than die in their burrows. The effect of toxic

substances produced by plankton is usually a human health hazard rather

than a cause of death to marine life. Phaeocystis produces the sulphur

compound

dimethyl sulphide. This can cause increased atmospheric

sulphur levels locally.

Aquarists rarely keep Heart Urchins,

but Shore Urchins, Psammechinus miliaris have proved intolerant

of low oxygen levels when compared to invertebrates of a similar size including

crabs. They are also intolerant of rapid temperature changes and will die

instantly if placed in water 5°

C warmer than they originated from.

Shore

Urchin,

Psammechinus miliaris

Shore

Urchin,

Psammechinus miliarisHEART URCHIN

Biological Notes

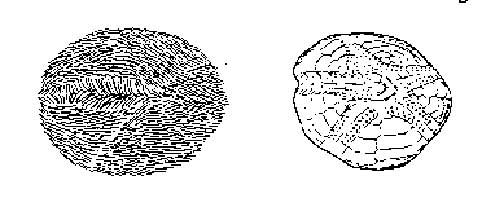

Alive Heart Urchin Dead

The Heart Urchin, Echinocardium cordatum, is a burrowing sea urchin common in fine sand around the British coast from the lower shore to deep water, recorded to depths of 230 metres. It has a thin elongate shell (called the 'test') with a distinct, slightly grooved front end giving it a somewhat heart-shaped outline. The spines are quite short and numerous, and flattened, particularly on the underside: a Heart Urchin placed on the surface of the sand will use its spines to push sand out and back from underneath the test so that it moves forwards and downwards, burrowing until it is 5 cm or more below the surface.

Behaviour

It uses long tubefeet to keep open

a narrow hole which opens at the sand surface in a conical depression;

clean water for respiration is drawn down this respiratory funnel. The

tubefeet also collect organic material and algae-coated sand grains from

the sand surface as food. As the Heart Urchin burrows slowly forward a

new respiratory funnel is opened in the sand and the old one allowed to

fill in.

There are no teeth in the Heart Urchin, unlike the symmetrical Edible Urchin, Echinus esculentus and the Shore Urchin, Psammechinus miliaris which have five plate-like teeth for shredding algae. The teeth and the complex apparatus which operates them is called the Aristotle's Lantern.

After death, the spines fall off and the delicate bleached white tests of the Heart Urchin may be washed ashore and found on the sand at low tide or on the strandline.

A similar species, Spatangus

purpureus, called the Purple Heart Urchin, buries itself in coarse

gravel.

Fossils

Fossil Heart Urchins of flint, belonging

to the genus Micraster, are occasionally found on pebble beaches

and buried in chalk deposits, and are known as Shepherd's Crowns. Micraster

that lived in the Upper Cretaceous period about 85 million years ago was

very similar to the species alive today.

Taxonomy

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Class: | Echinoidea |

| Order: | Spatangoida |

| Family: | Spatangidae |

| Genus: | Echinocardium |

| Species: | cordatum (Pennant) |

|

|

|

|

|

News 2000 |

Membership Form |

|