|

|

|

A

MASS STRANDING IN TORBAY

by Chris Proctor

On Sunday the 12th September 1993 south-west England was hit by a deep depression moving in from the Atlantic. The resulting gale was not particularly heavy (wind speeds of 60 mph were reported at Berry Head that evening), but the wind direction was unusual. The position of the depresson, with it's centre to the south of Britain, meant that the wind blew from the east, straight into Torbay. Most gales in this part of the country are caused by depressions passing to the north and blow from the south-west, leaving the bay sheltered. Conditions were spectacular. At Hope's Nose a 3 metre swell broke over the rocks, producing plumes of spray perhaps 10 metres high. A heavy surf was breaking on the beaches at Paignton and even in the most sheltered corners of Torbay the sea was rough. The following day the wind veered to the northeast and abated somewhat: by Tuesday the 14th the gale had ended.

Damage

The direction from which this gale blew meant that it's full force was felt along a stretch of coast normally sheltered from heavy weather. In several ports in the southwest, there was extensive damage to boats in normally sheltered anchorages. Little damage was reported in Torbay (except the iron railings beside the Shoalstone open air swimming pool which were swept away), but the effect on marine life was spectacular. Over the next few days I visited the beaches between Broadsands in the south and Torre Abbey Sands to the north to see what had been washed up. At all the beaches visited large amounts of material had come ashore, but by far the most impressive stranding was at Preston Sands just north of Paignton. Here the beach was an amazing sight. Much of it was buried under piles of weed, and near the north end massive drifts of dead animals, mostly molluscs, had accumulated. A wide variety of animals had been washed up: the more interesting species are discussed in detail below.

Molluscs

From the nearby rocks came thousands of Common Mussels,

Mytilus edulis, and a variety of other animals, mostly common shore

inhabitants such as Shore and Edible Crabs Carcinus

maenas and Cancer pagurus, and

the Green Sea Urchin Psammechinus miliaris. A few were probably

derived from rocks below low tide mark, including a Ballan

Wrasse Labrus bergylta, and the tail end of a Spiny Squat-Lobster

Galathea strigosa.

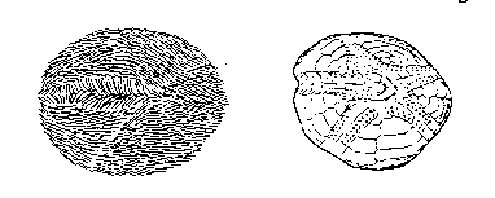

Psammechinus

miliaris

Psammechinus

miliarisMost of the stranded animals, however, came from the sandy seabed offshore

from the beach. These were much more exciting since many of them were sublittoral

species not normally found on the shore and included burrowing forms rarely

or never seen by divers. Most obvious were bivalve molluscs. The beach

was littered with thousands of Otter Shells Lutraria lutraria

and Razor Shells Ensis siliqua.

Scallops and Necklace Shells

The otter shells in particular excited much interest and virtually everyone I spoke to on the beach commented on them, many saying they had never seen them before. They are deep burrowers, maintaining contact with the surface by their massive non-retractible siphons, and are normally safe from storms. Their presence in such numbers showed that the waves had eroded deeply into the seabed, exposing and washing them out. Other bivalves washed up included another deep burrower, the Blunt Gaper Mya truncata, fair numbers of the spectacular Red Nose or Spiny Cockle Acanthocardia tuberculata with its vivid scarlet foot, and the little circular white bivalve Mysia undata. About half a dozen other species were present in smaller numbers.

Together with the bivalves were the burrowing gastropods which prey

on them. The commonest was the Large Necklace Shell Lunatia catena,

some of which were still alive and would probably have been worth collecting

for aquarium study. Also present were two burrowing predatory opisthobranchs.

I found several dozen Philine aperta in pools near low water

mark, looking rather repulsive like small grey slugs.

Other burrowers included a variety of echinoderms. Most familiar was

the Heart Urchin Echinocardium cordatum

which frequently washes up in Torbay and occurs on the shore in some places.

A few were freshly dead, but most were empty tests which had lost their

spines, probably individuals which had died some time ago and remained

buried in the sand until washed out by the storm.

Another group of species comprised animals which had lived on the surface of the sand. Prominent were Queen Scallops Aequipecten opercularis, and one or two Great Scallops Pecten maximus. Many of the Queen Scallops supported tangled masses of the calcareous tube worm Serpula vermicularis. Serpula was also present encrusting old whelk shells with Slipper Limpets Crepidula fornicata and a few Saddle Oysters Anomia ephippium. These shells had probably been inhabited by large hermit crabs: had they been empty it is unlikely they would have stayed on the surface of the sand long enough to gain such a rich encrusting fauna. The most likely inhabitant of these large shells would be Pagurus bernhardus, and this species was indeed present in fair numbers, although mostly as smaller individuals. Two smaller species were also present: Pagurus prideauxi with its symbiont anemone Adamsia palliata and the left clawed hermit crab Diogenes pugilator.

True Crabs (Brachyura)

True crabs were well represented with 9 species washed up, including

most of the common shore forms. Several species characteristic of sandy

bottoms were present.

Masked

Crabs washed up dead

Masked

Crabs washed up deadOther beaches produced much less variety than Preston sands, but some

new species were found. At Goodrington Sands few otter or razor shells

had been washed up, but there were plenty of spiny cockles. At Broadsands

at the southwest corner of Torbay burrowing fauna was conspicuously scarce.

There were many sagartiid anemones here, which had probably been living

attached to stones and shells covered by a thin layer of sand. The real

interest was opisthobranch molluscs. In addition to a few Sea Hares

Aplysia

punctata and large numbers of Philine aperta, hundreds

of another shelled opisthobranch, Akera bullata had been

stranded. These have a very delicate translucent brown shell that is so

thin it can bend without breaking. Akera is known to occur in plagues

in some years: presumably this was such an aggregation, possibly to breed

- there were many spawn ribbons washed up with them, though these might

have belonged to a different species.

Sand Dwellers

At the northwest corner of Torbay at Torre Abbey Sands, there were many

live Heart Urchins Echinocardium cordatum,

and the small Sand Crab Portumnus latipes, like a swimming

crab with a very narrow carapace.

Sea Bed Erosion

Looking at the distribution of the stranded animals some patterns are

obvious, but there are also some puzzles. Clearly Preston Sands took the

brunt of the weather, with deep erosion of the sea bed which dug out even

the deepest burrowers. To the south the depth of erosion decreased, so

that at Goodrington only shallow burrowers such as spiny cockles were washed

up in any numbers and at Broadsands the stranded fauna comprised mainly

surface dwellers. The level of Broadsands beach actually rose, burying

a patch of stones near the south end. At Torre Abbey Sands some erosion

took place, exposing the forest bed and digging out many heart urchins.

Heart

Urchin

Heart

Urchin

|

|

|

|

|

News 2018 |

Membership Form |

|

|

Use these links if your are familiar with the scientific classifications of marine life |